In Conversation – Black History Month

This is a repost of a blog jointly written by CRER and the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah RACE Centre and Educational Trust, originally published on the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah RACE centre’s website on the 14th of December 2022.

In June 2022, Maya Sharma, Ahmed Iqbal Ullah RACE Centre’s Collections Engagement Officer, took part in a Black histories workshop also attended by Nelson Cummins, Communities and Campaigns Officer at the Coalition for Racial Equality and Rights. Through their conversations during the event, they established that their organisations, despite working in different locations (Manchester and Glasgow) and different ways, had very similar same core values and aims. They also found themselves talking about their approaches to working with Black and Global Majority histories.

These conversations continued by email as they looked ahead to Black History Month 2022, discussing their approaches to BHM and the limitations of BHM as a vehicle for education and change, as well as why BHM is still important. We thought it interesting to share highlights in this joint blog.

_________________________________________________

Dear Nelson,

We talked a little about Black History Month (BHM) but didn’t go into any detail about our planned activities for 2022. This year we are exploring Manchester Caribbean Carnival, which is 50 years old this year (or 51 years, as this date is contested!). We have some really special archive collections relating to the history of Manchester Carnival, as well as publications in our Local Studies collection and our library. We’ll be putting these to work, inviting people to explore the history and significance of Carnival.

We’ve chosen this theme not only because of the milestone year but also because it is such an important and significant cultural event. We approach Carnival carefully, as it is often presented in simplistic ways, feeding into the “steel pans, saris and samosas” approach to Global Majority histories. I’m sure you’re very familiar with this! Simplistic and reductive narratives, ignoring the complexity and diversity of local histories, and glossing over or avoiding painful or difficult experiences.

For us, Carnival is of course an explosion of joy and celebration and draws on rich cultural traditions. It’s also about asserting a right to be and to occupy space. And you can’t talk about Carnival in any nuanced way without talking about racism – the lack of value placed on Caribbean art and culture, the way communities have had to fight hard for space to celebrate Carnival, and of course policing. So there is so much to explore and we try to do this in thoughtful ways.

But what about CRER – what do you have planned, what’s your approach? And I’m really interested that you work with Black-political too. Could you say anything about this?

Maya

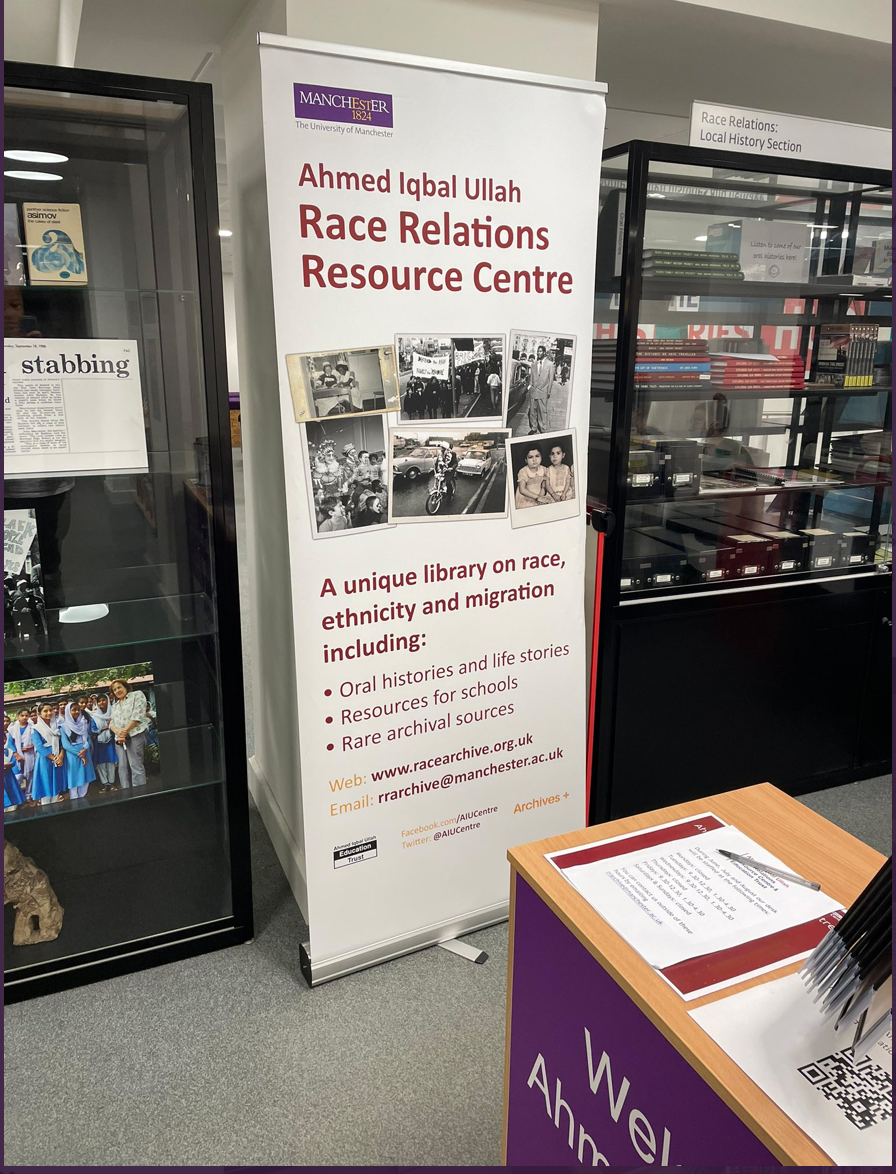

Image from the race archives and race relations library in the Ahmed Iqbal RACE Centre

————————————————————————————————————————————–

Hi Maya,

That all looks great to me. Really interested to see more of what you have planned around the carnival, it seems an integral part of local Black history in Manchester to explore.

We have a real range of events planned, including those we are delivering and those submitted to us for inclusion in our collaborative programme by a range of partners. This includes submissions from grassroots community organisations to larger national heritage organisations. We have walking tours, exhibitions, talks, film screenings and many other events planned.

Our approach to adopting a Black-political take on BHM is rooted in the history and legacy of the approach to Black History Month in the UK. As I’m sure you are aware the first UK Black History Month was launched in October 1987 by the Greater London Council (GLC) thanks to the efforts of Ethnic Minorities Unit staff Ansel Wong and Akyaaba Addai-Sebo, along with Cllr. Linda Bellos, Cllr. Narendra Makanji and Deputy Leader of Education, Bernard Wiltshire[i].

Whilst stressing that African history was very much central to Black History Month in the UK, Ansel Wong explained the broader context: “Some have questioned our use of the term “Black” instead of “African”. We deliberately chose to call it “Black” as Black posited and reflected tolerance and acceptance of the enriching cultural diversity of contemporary British society. Black is also a unifier term that brings into sharp relief the various strands of suffering, humiliation, exploitation and denigration as well as an articulation of solidarity and the building of allies in relation to shared and common experiences.”

In Scotland, we follow the same model, and CRER has co-ordinated a uniquely Scottish Black History Month during October since 2001. This encompasses the history of African, Caribbean and Asian people in this country; people who often have a direct link with Scotland through slavery, colonialism and migration. Black History Month focuses on people whose sacrifices, contributions and achievements against a backdrop of racism, inequality and injustice are often forgotten about.

Best wishes,

Nelson

Image of a walking tour of Glasgow that took place as part of BHM Scotland 2022

————————————————————————————————————————————–

Hi Nelson,

Good to know more about your approach to BHM. I love the collaborative programme; this way of working allows for a real variety of types of events, audiences and perspectives. Which in turn, pushes back against attempts to homogenise Global Majority people and histories.

Thanks also for talking about the use of Black-political. This sent me off down an internet rabbit hole this morning, looking at the different views and approaches to describing race and ethnicity, and particularly: how we talk about ourselves collectively. There are so many arguments for and against the use of Black-political, and then of course, if we don’t use this term, how do we talk about ourselves collectively? At the RACE Centre we have recently started using the term Global Majority when we are speaking about ourselves collectively.

Personally, I feel quite conflicted about this: I can appreciate the very many different views. Yes, Black-political is a powerful way of standing together in the face of racism and Othering; it’s also a way of connecting our specific struggles and campaigns. But it can also lead to an artificial homogenisation of our experiences and heritages, and can ignore (or deny) that some groups experience racism in much acute ways: 5.3% of Black people experienced stop-and-search policing compared to 1.8% of Asian people, for example. People of Bangladeshi heritage have far worse health outcomes than those of Indian heritage and other ethnic minorities.

I started wondering about the different nature of our organisational histories and that of our Black / Global Majority communities, north of the border and here in Greater Manchester. Is it possible that where Global Majority communities are smaller and concentrated in a few areas (please tell me if this is an inaccurate description of Scotland’s Global Majority population!), the desire to stand together and connect experiences politically is more compelling than it might be here in Greater Manchester, where perhaps the different Global Majority communities have had the luxury of developing their own localised infrastructure, networks, community groups and so on?

I look forward to your response.

Maya

————————————————————————————————————————————–

Thanks Maya,

I think what is quite interesting about Scotland, is that while it is not necessarily a country with a high overall Black or minority ethnic population, it has several cities that have quite a high minority ethnic population that is growing. For example, Glasgow’s minority ethnic population is around 15% but 1 in 4 primary school children are from a Black or minority ethnic background so the population is definitely growing as Scotland as a country becomes more diverse.

I do think that in the UK politically-Black as a term has power in recognising grounds for solidarity, especially when thinking about histories that can often be connected through slavery, empire, colonialism and migration. I think we would use it from that perspective as a way to organise politically (similar to civil rights movements of the 60s and 70s), while still highlighting diversity and issues such as anti-Black racism too.

I do wonder however, if Manchester is a slightly different context in having a longer established larger Black community than Glasgow? and if Glasgow may trend that way over time?

Cheers,

Nelson

————————————————————————————————————————————–

Hi Nelson,

Really interesting, what you shared about Scotland growing and becoming increasingly diverse. I think that makes the work you’re doing all the more important: ensuring young Black and Brown Scots can see themselves and their heritage reflected in education, the heritage sector and the world around them.

So, going back to Black History Month – when we talked we acknowledged both the limitations and the opportunities it offers. Shall we start by talking a bit about the frustrations? For me / us, this is mostly that many organisations seems to funnel all and any activity connected to Blackness or anti-racism into October. We get so many requests to take part in events or to supply resources, information, knowledge etc during October – we are already really busy with our own activities! We also observe that a lot of BHM activities seem to be quite simplistic – people seem to shy away from nuance and complexity, as well as from talking about racism and discrimination. We’d like to see explorations of Black histories that include celebratory approaches (there’s so much joy in our histories) but also doesn’t flinch from talking about “difficult” themes like racism and discrimination. And that don’t end on 31st October!

Maya

————————————————————————————————————————————–

Thanks Maya,

Important issue to raise. I think for us the challenges are similar really. We’re aiming for BHM to have a political and campaigning aspect to it, so we’re using the profile given to the month to raise and highlight historical and present day issues of racism, quite often through the lens of racism being a legacy of slavery, colonialism, empire, while balancing the space for celebration too.

I agree however that it is frustrating that a lot of the time the interest in Black history only comes during October and that is a challenge to work with and can leave us with similar feelings of feeling stretched and trying to fit lots of different requests in.

Kind regards,

Nelson

————————————————————————————————————————————–

Hi Nelson,

I absolutely agree with you: BHM gives us the opportunity to ask about why we need a Black History Month, and how we can get to the point where Black histories are widely valued, explored, celebrated and appreciated and seen as a natural part of the UK’s history.Countless activists and organisations ask these questions throughout the year of course, but BHM does give us a little more space for this and sometimes access to platforms we don’t usually get…

Another positive for me is that whilst many people come to us with last minute requests or poorly thought-out activities, this does provide an opening to work with them on this. We can gently and clearly explain the problems with this kind of attitude and invite them to approach Black histories in ways that centre Black people and their diverse histories and perspectives. Working with more mainstream organisations can mean reaching people that don’t perhaps engage with organisations like ours.

Maya

————————————————————————————————————————————–

We hope that sharing some of this exchange of ideas has inspired our readers to think about the wider issues around Black History Month and the way we as organisations and individuals approach it.

[i] https://www.blackhistorymonth.org.uk/article/section/real-stories/the-radical-and-transnational-roots-of-black-history-month-in-britain/